I’m white, so I can’t use the word “nigger.” To do so today automatically brands me in everyone’s eyes as a racist—at least a suspect or latent one.

You’re black, so you can use the word without stigma anywhere or at anytime—especially if you’re out to ruffle my comfort level. In fact, if you’re Chris Rock, you can flaunt it often, loudly, and widely—and make millions of dollars doing it. During any of his sexually-based, racially top-heavy routines, no one will mind if I laugh at the “n” word, but once outside the theatre, I’m not permitted to.

Just as Detective Mark Fuhrman found out on the witness stand in O.J. Simpson’s

murder trial, despite his testimony that he’d never used the “n” word in his life, no one believed him for a second. Why? Because he was white (and a police officer). His denial so infuriated prosecutor Marcia Clark and her black assistant, Christopher Darden, they decided to wander off into one of the trial’s many distractions to prove Fuhrman had actually used the forbidden word. Their sleuthing soon dug up a tape on which Fuhrman was heard using . . . . Aha! See! That proves white guys are thinking and using the “n” word behind our backs! While this revelation discredited Fuhrman’s testimony concerning his personal language habits, it actually cast a negative light on the prosecutors and may have subtly influenced jurors’ attitudes during their final deliberations.

murder trial, despite his testimony that he’d never used the “n” word in his life, no one believed him for a second. Why? Because he was white (and a police officer). His denial so infuriated prosecutor Marcia Clark and her black assistant, Christopher Darden, they decided to wander off into one of the trial’s many distractions to prove Fuhrman had actually used the forbidden word. Their sleuthing soon dug up a tape on which Fuhrman was heard using . . . . Aha! See! That proves white guys are thinking and using the “n” word behind our backs! While this revelation discredited Fuhrman’s testimony concerning his personal language habits, it actually cast a negative light on the prosecutors and may have subtly influenced jurors’ attitudes during their final deliberations.What’s going on here?

Could it be that “learned” behavior (as opposed to “innate” behavior), which modern psychology asserts is ultimately influential in the development of our personas, hasn’t been influential at all? That is to say, people’s thought processes seem not to have been altered by forbidding their use of certain emotion-laden words that are inherent in our vocabulary.

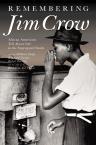

Jim Crow reborn? In fact, could it be that suppression of certain verbal habits is actually creating an undesirable internal backlash--a modern form of Jim Crowism?

During the 60s when the “consciousness” of American black culture was “being raised”

by Martin Luther King and more militant organizations like the Black Panthers, American English progressed rapidly through a linguistic evolution when confronted with trying to level the racial differences playing field. “Negro” was discarded in favor of “black,” which soon gave way to the current preference: Afro-American. (I suspect that, if semanticists could only invent a word that doesn't arouse the mock cynicism of European whites who are tempted to describe their ancestry as “I’m a Anglo-American,” or “I’m a Danish-American,” or "I'm Slovenian-American," Afro-American would be on the way out.)

by Martin Luther King and more militant organizations like the Black Panthers, American English progressed rapidly through a linguistic evolution when confronted with trying to level the racial differences playing field. “Negro” was discarded in favor of “black,” which soon gave way to the current preference: Afro-American. (I suspect that, if semanticists could only invent a word that doesn't arouse the mock cynicism of European whites who are tempted to describe their ancestry as “I’m a Anglo-American,” or “I’m a Danish-American,” or "I'm Slovenian-American," Afro-American would be on the way out.)So after almost half a century, if us white guys are still thinking and occasionally verbalizing the "no-no" words in private, could it be that we’re still no closer to solving the “race problem” in this country than we were when Lincoln signed the Emancipation Proclamation? Is it possible that Linguistic Political Correctness (LPC) is primarily aimed at white guys and gals and is behind a half-century period of gestating frustration that could manifest itself as a sudden cultural backlash?

Is Dr. (PhD) Bill Cosby on to something when he talks to audiences of black parents, te

achers, and kids and lambastes them for clinging to and even inventing more layers of negative social habits that retard their assimilation into the American cultural mainstream? Cosby has especial disdain for black “street language” which a couple of California school districts have attempted to legitimize by labeling it “Ebonics” and including it in the schools’ curriculum as an “alternative” form of English language (if you can believe our educational system has sunk so low--more on this later).

achers, and kids and lambastes them for clinging to and even inventing more layers of negative social habits that retard their assimilation into the American cultural mainstream? Cosby has especial disdain for black “street language” which a couple of California school districts have attempted to legitimize by labeling it “Ebonics” and including it in the schools’ curriculum as an “alternative” form of English language (if you can believe our educational system has sunk so low--more on this later).But back to my theme: Are we white guys silently reacting to the semantic repression that has been imposed on us since the 1960s? Is this repression already causing even wider rifts of resentment between the races, instead of altering the tendency toward racial bias? If so, are we actually developing a higher, more pernicious attitudinal barriers between the races? Despite all the advances the black community has achieved the past half-century, black organizations such as the NAACP cite statistics which demonstrate the advances have not been proportionate to their percentage of population in any measurable area.

This unique American linguistic dilemma has spread to relations among other races as well

. Take the case of Chai Vang, at this moment on trial for slaying six white hunters with his high-powered hunting rifle. Chai is a Muong tribesman from Laos who immigrated to Wisconsin more than 20 years ago, but found assimilation among the heavily Germanic stock was not easy. Apparently, the slain hunters and Chai had had many run-ins over the years in various settings, but this time Chai exploded when they encountered each other while deer hunting. The exact circumstances of the encounter are not clear—the ongoing trial is attempting to determine this. However, it is known that their previous encounters were always laden with tension and just enough insults (“slant-eyes,” “gooks,” and similar Vietnam-era verbiage) uttered under their breath that an unhealthy relationship evolved over the years, exploding during early evening hours last year.

. Take the case of Chai Vang, at this moment on trial for slaying six white hunters with his high-powered hunting rifle. Chai is a Muong tribesman from Laos who immigrated to Wisconsin more than 20 years ago, but found assimilation among the heavily Germanic stock was not easy. Apparently, the slain hunters and Chai had had many run-ins over the years in various settings, but this time Chai exploded when they encountered each other while deer hunting. The exact circumstances of the encounter are not clear—the ongoing trial is attempting to determine this. However, it is known that their previous encounters were always laden with tension and just enough insults (“slant-eyes,” “gooks,” and similar Vietnam-era verbiage) uttered under their breath that an unhealthy relationship evolved over the years, exploding during early evening hours last year.Is it possible that Linguistic Political Correctness (LPC) was actually the basic cause of the profound levels of resentment in both new immigrants and local citizens? Were the two sides actually prevented by LPC from communicating with each other honestly and openly about their prejudices, problems, and lifestyles? And had they been able to freely communicate with each other when Chai and his family entered the community, would that have contributed to forging a different, less violent attitudes?

If anyone doubts the power of spoken words, they need only remind themselves how their own emotions can be quickly raised to fever pitches under the most ordinary situations—a real or perceived slight to you or your family can bring most people unglued. But just how quickly an appropriate explicative or a good "chewing out" (even if not in the person's presence) can bring beneficial cathartic release—defusing the frustration. It’s easy to imagine the internal pressures that would build internally if we were required to repress our reactions during the course of these ordinary situations, multiplied in frequency over time—that is, to pretend nothing had happened. Yet that's what happens to a lot of us ordinary users of language.

A Polish-born professor of linguistics, Alfred Korzybski, broke new grounds in semantics between 1920 and 1940 with a unique theory of how people function--"General Semantics," only tangentially related to semantics as we usually think of it. He described how most people, unless taught how to deal consciously with the psychology of words, “reify” them—that is, they actually try to transform words into reality by over-identifying with what they think they mean (or what they'd like them to mean) and then try to live and force others to also live accordingly. Professor Korzybski laid a foundation for a mod

ern generation of semanticists such as S.I. Hayakawa who tried to teach people how to apply the adage in their daily lives, “Sticks and stones won’t break . . . . etc.” Or as Alice wondered in her conversation with Humpty Dumpty, "The question is, whether you can make words mean so many different things." To which Humpty Dumpty answered knowingly, "The question is, which is to be master—that’s all."

ern generation of semanticists such as S.I. Hayakawa who tried to teach people how to apply the adage in their daily lives, “Sticks and stones won’t break . . . . etc.” Or as Alice wondered in her conversation with Humpty Dumpty, "The question is, whether you can make words mean so many different things." To which Humpty Dumpty answered knowingly, "The question is, which is to be master—that’s all."During a very critical period of social development in the U.S. (the 1950s and 1960s) people weren't very interested in and today show just as few signs of wanting to learn these critical skills. Most of us, when cornered, continue to adopt a confrontational attitude, elaborated by the Queen (was it?) in The Adventures of Alice in Wonderland who told Alice defiantly: "Words mean just what I want them to mean."

Unfortunately, semantics has remained the province of the academy. Perhaps, had it been seen as a vital “real life” skill to be widely taught to our kids, Chai Vang wouldn’t be on trial for murder today. In fact, it is possible to surmise realistically that the level of antagonism between people and races might have been significantly lowered--had we understood how not to “reify” words in the course of our everyday conduct, which is shaped largely by words, i.e. person-to-person communication.

More lamentable is that Washington's officialdom, the U.S. Commission on Civil Rights--charged with implementing the many tiers of non-discrimination policies, regulations, and laws involved in affirmative action programs--didn’t understand the dangers of verbal “reification.” So they gave us the platitudinous, "We mustn't use words that hurt" (indelicate, rude, inappropriate, vulgar, race-baiting). So all the well-meaning, but linguistically uninformed citizens drew up a list of words that might "hurt" someone. Thus was born Linguistic Political Correctness.

Would there have been a different outcome if our “Great Society” leaders had known something about semantics? Instead of purging our language lexicons of “inappropriate” language, what if they had promoted the publication and distribution—at the community level—of "rules" relating to human behavior and language? Might this approach have underwritten a different outcome in our interpersonal relations today?

Look again at Chris Rock’s routines that play on his audience’s discomfort with racial biases by repeatedly using and re-using “forbidden” words. Doesn’t he lower the pressures among everyone listening to him, if only for an hour or so?

Or take Ann Coulter, while leaving obscenity to Chris Rock, who makes a simil

ar breakthrough in her books and TV appearances by talking bluntly about political undercurrents that LPC effectively represses. By daring to throw those things in our faces and by using "no-no" language that political antagonists aren't used to hearing, Ann manages to arouse levels of emotion that aren't normally displayed among "sophisticated" politicos on radio and TV--she's not healing, but deliberately applying semantics in order to antagonize and agitate--a useful outcome in many circumstances. She proves that the sword can cut both ways! (Ann and I are both NJC alums--we were only a few months apart, but look where we ended up . . . as I write this blog to myself!)

ar breakthrough in her books and TV appearances by talking bluntly about political undercurrents that LPC effectively represses. By daring to throw those things in our faces and by using "no-no" language that political antagonists aren't used to hearing, Ann manages to arouse levels of emotion that aren't normally displayed among "sophisticated" politicos on radio and TV--she's not healing, but deliberately applying semantics in order to antagonize and agitate--a useful outcome in many circumstances. She proves that the sword can cut both ways! (Ann and I are both NJC alums--we were only a few months apart, but look where we ended up . . . as I write this blog to myself!)Might today's “offensive” words have become less insulting had we learned about their emptiness? Might we have developed a whole different approach to understanding each other had we learned something about the words we use? It’s probably too much idealism to wonder whether such an open approach to language might have led to positively altered behavior among people with racial and other differences? We could not have done worse.

No comments:

Post a Comment