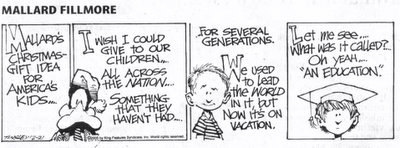

So what's the problem with American education? "Problem? What problem?" Believe it or not, there are a few people who deny that there's a problem. If you've never talked to kids or their teachers during the past 20 years, you might think everything's A.O.K. However, confronted with overwhelming evidence to the contrary, as our own personal experiences will testify, and as revealed in the endless reams of statistics being kept under President Bush's federal program "No Child Left Behind" (and other state-level programs), I think it's safe to conclude that our system's broken.

So what's the problem with American education? "Problem? What problem?" Believe it or not, there are a few people who deny that there's a problem. If you've never talked to kids or their teachers during the past 20 years, you might think everything's A.O.K. However, confronted with overwhelming evidence to the contrary, as our own personal experiences will testify, and as revealed in the endless reams of statistics being kept under President Bush's federal program "No Child Left Behind" (and other state-level programs), I think it's safe to conclude that our system's broken. - We know there's a problem when students trash their schools and disrespect their teachers--even resorting to physical violence.

- We know there's a problem when psychologists report one out of 10 teens suffer clinical depression.

- We know there's a problem when 25% of high school youngsters don't graduate.

- We know there's a problem when the U.S.A. is 39 out of 50 nations tested in basic academic skills.

- We know there's a problem when universities have to lower standards in order to fill seats in freshman classes, and then have to create remedial courses in basic courses in order to prepare them for university-level work.

- We know there's a problem when employers complain that American universities are not graduating enough scientists and engineers to fill their positions, requiring them to turn to India, Russia, England, and other countries.

- In summary, the evidence is overwhelming, so we needn't argue if there's a problem, but must turn to solving the problem: Why is our once famous educational system broken?

Doing so isn't easy--the problem is so large and involves hundreds of thousands of teachers, admin

istrators and support people who deliver something we've labeled "education" (it's the largest industry in the U.S.A.), it's hard to "get one's arms around it." It's appropriate to use the adage of the blind men who were told to feel an elephant and then report what it was they examined. Each of them was able to relate bits and pieces of their "feelings" and "impressions," but until someone was able to help put the pieces together that make up a coherent picture, the elephant tended to remain a mysterious entity--threatening and revolting to some, curious and bizarre to others. So to begin shaping the nature of the beast, we must have a common basis for understanding what it is we're "feeling".

istrators and support people who deliver something we've labeled "education" (it's the largest industry in the U.S.A.), it's hard to "get one's arms around it." It's appropriate to use the adage of the blind men who were told to feel an elephant and then report what it was they examined. Each of them was able to relate bits and pieces of their "feelings" and "impressions," but until someone was able to help put the pieces together that make up a coherent picture, the elephant tended to remain a mysterious entity--threatening and revolting to some, curious and bizarre to others. So to begin shaping the nature of the beast, we must have a common basis for understanding what it is we're "feeling".It's very helpful to review briefly our own history, which impacts significantly on our system like no other country in the world. When our much revered forefathers set out to establish a new country free of King George III's tyranny, we inherited essential British attitudes and a system of education that was mostly a privilege of the "upper crust." Education had always been a private matter delivered by families of the privileged classes who hired learned tutors in philosophy, religion, mathematics, Latin, and science. Education was rarely something delivered to women, who instead were taught the "social graces" by their mothers. However, the enlisted men who fought and suffered the years of our struggle with Great Britain were largely "dumm as drumsticks" to quote a patrician in those days. They were mostly farmers and tillers of the land, with a smattering of shopkeepers--socially barely one step upward. Their officers, of course, were educated and members of the privileged classes.

Historically, education for the masses was an unthinkable notion--even by the most enlightened liberal thinkers--until the Industrial Revolution began to demand specific factory skills of workers--more than those possessed by farmers and tillers of our agrarian society. In response, beginning in Europe, formal, organized education began to take shape to fill these needs. Simultaneously in America there arose a school of thought that had been influenced, quite understandably, by a revolutionary idea that followed from the successful American political revolution--the republican (note, in the small 'r' meaning) notion that education belonged to "the people"--a notion that was born in the Declaration of Independence's opening paragraphs:

"We hold these Truths to be self-evident, that all Men are created equal, that they are endowed by their Creator with certain unalienable Rights, that among these are Life, Liberty, and the Pursuit of Happiness--"

The flowering of this sentiment occurred in massive numbers after World War II when, in an effort to absorb into the economy the millions of GIs being mustered out of service, the once-cloistered universities, heretofore reserved mainly for the privileged, were opened to anyone with the money to pay the tuition--and the generous GI Bill supplied millions of young veterans just that.

It followed quickly that high schools opened their doors to a wider segment of the population--even if it meant readjusting its standards to accommodate more students. Until the early 1950s, high schools and universities filled the demand of America's voracious need for managers, technicians, scientists, engineers, and most facets of the liberal arts professions: psychologists, sociologists, librarians, statisticians, and yes . . . teachers. At the university level, the curricula were shaped and aimed at society's needs and qualified students became "experts" through a rigorous and demanding process. High schools too aimed their students to become proficient in the essential building blocks: math, reading, science, with a smattering of the "old" subjects like Latin, Greek, philosophy and (in parochial schools) religion.

But things began to go horribly wrong around the late-1950s. Some say a national psychosis was introduced into our cultural psychology by the apocalyptic fears that came with the nuclear age in Cold War with the Soviet Union was behind the New Age--a national mode of escapism, as it were. Whatever the reasons, respectable liberal thinkers began to consider--in all social affairs of the nation--the impact of the words, "All Men are created equal . . . and are endowed with certain unalienable Rights . . . pursuit of happiness." A new political movement dedicated to implementing the ideas embodied in these words grew quickly--their proponents viewed school curricula too restrictive, both in their breadth and depth and in terms of the people shut out of the system for various reasons: poverty, political repression, class and race prejudice, and (although rarely voiced) native ability. They were able to shame people into silence, or were successful in shouting them down, if they persisted in resisting the "self-evident" truths in the words "all, created equal, unalienable Rights, pursuit of happiness."

Reality was replaced with excessive idealism by well-meaning progressive thinkers and their followers, but they became so enamored with the progressive ideas embodied in those words t

hat the balance between theory and reality was lost in the enthusiasm of a new era. That enthusiasm was given a sudden, enormous political boost in the 1960s by JFK's era dubbed "Camelot" and the "Age of Aquarius" (the "me" Age) by their most dedicated practitioners. Reinforcing this "new era" was the music and dress code of the Beetles and their imitators; "pot" and peyote were recommended by Timothy Leary and other darlings of the "New Age" as a way to experience "mind opening." Free love, imported from daring films and books from socialist Scandanavia, was institutionalized in a new Hollywood genre of porn in films like "Deep Throat." Widely practiced among hippies of the time, it was undoubtedly encouraged by the invention and introduction of the "pill" in the 1960s.

hat the balance between theory and reality was lost in the enthusiasm of a new era. That enthusiasm was given a sudden, enormous political boost in the 1960s by JFK's era dubbed "Camelot" and the "Age of Aquarius" (the "me" Age) by their most dedicated practitioners. Reinforcing this "new era" was the music and dress code of the Beetles and their imitators; "pot" and peyote were recommended by Timothy Leary and other darlings of the "New Age" as a way to experience "mind opening." Free love, imported from daring films and books from socialist Scandanavia, was institutionalized in a new Hollywood genre of porn in films like "Deep Throat." Widely practiced among hippies of the time, it was undoubtedly encouraged by the invention and introduction of the "pill" in the 1960s.Nietzsche's nihilism was reflected in Time Magazine's April 8, 1966 cover that asked "Is God Dead?"

Karl Marx again became fashionable on university campuses, creating a newly minted political movement that quickly spawned a spate of radical factions of every imaginable kind, including the "Symbionese Liberation Army," a small group that kidnapped newspaper heiress Patricia Hearst, who strangely became one of them and took part in Los Angeles area bank robberies. In summary, the 1950s and 1960s were decades of intense turmoil, vast national uncertainty, experimentation, and social and political bombast. It was during this social upheaval that "education for everyone" was considered deficient and outmoded--in terms of both curriculum and the methods of delivering it in the classroom. Experimentation became the main sail of the teaching profession.

Karl Marx again became fashionable on university campuses, creating a newly minted political movement that quickly spawned a spate of radical factions of every imaginable kind, including the "Symbionese Liberation Army," a small group that kidnapped newspaper heiress Patricia Hearst, who strangely became one of them and took part in Los Angeles area bank robberies. In summary, the 1950s and 1960s were decades of intense turmoil, vast national uncertainty, experimentation, and social and political bombast. It was during this social upheaval that "education for everyone" was considered deficient and outmoded--in terms of both curriculum and the methods of delivering it in the classroom. Experimentation became the main sail of the teaching profession.At Kindergarten through Grade 12 levels, "New Math" and "New Reading" methods were invented. No more sounding out words in learning reading--it was now said that "word recognition" was now "in." No more rote memorizing of "boring" multiplication and division tables--"cognitive understanding of these fundamentals was now "in." Curricula were delivered in a "free, less regimented" atmosphere in which kids could study what "felt right" for as long as they wished. Teachers were supposed to cater to the "needs" of their students; they were advised not to become "authority figures," but "facilitators of learning. Older teachers in the system were admonished to join this revolution and if they didn't, they were the first ones to be retired or advised to seek other employment. Education in the 1960s was profoundly changed by those who promoted the "It's all about me" generation that the Age of Aquarius had ushered in.

At the university level the liberal arts were also profoundly affected. Here, experimentation went to new levels. Teacher training was shaped in such a way as to make graduates with Bachelor and higher degrees vessels of the new educational philosophies and methodologies. "Social consciousness" became the raison d'etre of "higher" education; the New Age professors created new courses in racial sensitivies, cultural appreciation--in a word, the "basket weaving " courses. No need to bother students with "hard" courses such as algebra and calculus, chemistry or biology; instead, in order to fill the liberal arts graduation requirements, they were substituted with "introduction to mathematical principles" or "general philosophy" and in science, "history of science" or "appreciation of science" courses. In a word, this was truly the era that started the "dumbing down" of America.

Where we are today: Fortunately, most youngsters nurtured in this period have forgotten this era in meeting life's demands; today they look back on it with a certain nostalgia--either positive or negative, depending on how retarded their lives were because of their education in this era. During the past 10 years, a palpable trend has been underway--there is a slow, tortured desire to return to "the basics" at the K-12 levels--but you don't turn around a giant ocean liner on a dime; it takes time to build new keels and to reorient the ship toward a different course. The main exception to this "corrections trend" is in the liberal arts departments on most American university campuses where the Aquarius generation of "intellectuals" sought permanent haven as professors. Unlike "real life," the Ivory Tower makes few "real world" demands on professorial theorticians, so that their habitants today continue to live out their fantasies and--worse--infect the young and impressionable who enroll to seek "Truth," thereby delaying their maturity and entry into the "real America." Purging campuses of this generation will probably not be complete until they die out--literally.

At this point, you're either with me or not. If I haven't convinced (or reminded) you that America's educational system is truly broken, then don't bother reading Part 3 ("The Purpose") of this series. Instead, I suggest you direct part or all of your 2005 tax refund to your local School District to signal that you're happy with the way things are.